The recent articles published on this site show a never dormant and ill-concealed intolerant regurgitation towards the beliefs of others. Freedom of belief is protected by the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and by subsequent similar declarations, but in the light of the facts this right requires constant and further commitment, so that it is effectively recognized and respected as an inalienable right.

Below we publish an article by professor Massimo Introvigne, internationally renowned sociologist of religions, who gives an example of how easy it is to fall into intolerance and incitement to hatred.

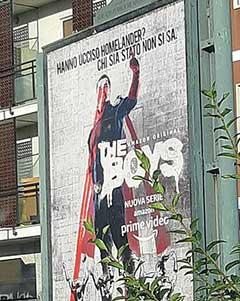

From Charlie Hebdo to “The Boys”: “Freedom of Expression” vs. Religious Liberty

Where exactly lies the limit between free speech and hate speech that offends members of a religion? Many discuss Charlie Hebdo—but it is not the only case. The Boys is another pop culture example.

by Massimo Introvigne, March 12, 2020 — For all those interested in religious liberty, one of the most important topics in recent weeks and months has been its possible conflict with freedom of expression. The mainline English-speaking media’s opposition to French President Emmanuel Macron’s stance has been analyzed as a latter-day incarnation of the century-old conflict between the French and Anglo-American notions of secularity.

The story is well-known. Bloody terrorist attacks have targeted the French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo and those who promote it, including a French high school teacher, who was beheaded on October 16. The magazine had published cartoons lampooning, with sexual and scatological innuendos, Prophet Muhammad, Islam, the Quran—as well as Jesus Christ and the Virgin Mary. British and American media, supported by the Vatican, criticized the cartoons as offensive, and promoting hate against religion, while President Macron hailed the French “right to blasphemy.”

Muslim demonstration in Paris against Charlie Hebdo cartoons (credit)

Three quite different questions got confused in the process. The first was whether violence and terrorism against those who offend a religious or ethnic group can be in some way justified. The answer is no. Nothing can ever justify violence and terrorism. Raising this question also plays into the hands of the terrorists themselves. As a scholar who has written books on both al-Qa’ida and ISIS, I know that such organizations first decide to attack a specific country, then look for targets against which they can deploy their propaganda tools, thus “justifying” terrorism. If there had been no Charlie Hebdo cartoons, the terrorists would have killed somebody else, just because the victims were Jewish, American, French, or simply in the wrong place at the wrong time. As but one example, none of the 2,977 victims of 9/11 had done anything to offend Islam.

The second question is whether courts of law should sanction those who, like Charlie Hebdo, offend religious communities. The answer is that it depends on both national legal systems and circumstances. French law is not American law. And there is a slippery grey area between hate speech and legitimate criticism or satire. On the one hand, the French cartoons used four-letter words and crude sexual depictions when dealing with the founders of the two largest world religions. At the other extreme, only a few Catholic radicals were offended by the poetic criticism of the Vatican in the TV series The Young Pope by award-winning director Paolo Sorrentino. But there are cases in the middle. While the present Pope is rumored to have been privately amused by Sorrentino’s series, when he served as Archbishop of Buenos Aires he was among those who went to court trying to prevent the public exhibition of paintings by leading Argentinian artist Léon Ferrari, depicting Jesus Christ and Pope John Paul II in a way many Catholics regarded as offensive. There is nothing wrong in seeking the opinion of courts of law in these matters. It is a civilized reaction, and one which defuses violence. What is important is that courts equally protect all groups, irrespective of their minority or majority status or popularity.

A third, different question is whether quality media and those who shape opinion and culture should support or condemn speech, including fiction and satire, likely to fuel hate and prejudice against a religion. In 2011, I served as the Representative of the OSCE (Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe, of which the U.S. is also a participating member) for combating racism, xenophobia, and religious intolerance. Part of my portfolio was coordinating the OSCE’s response to hate speech, and I encountered daily situations where the border between hate speech and freedom of expression was unclear. At that time, it was often the U.S. that pleaded for a larger protection of freedom of expression, with Western European countries being more restrictive when free speech was invoked to justify racism, anti-Semitism, or Islamophobia.

There is one paradigmatic case illustrating these problems. It concerns the American TV series “The Boys,” airing since 2019 through Amazon Prime Video. It is a free adaptation of a comic book by the same name by Garth Ennis and Darick Robertson. The authors are known for their penchant for provocation, and for turning modern cultural myths on their heads. While superheroes are generally regarded as role models, “The Boys” are members of a vigilante group devoted to exposing the fact that superpowered individuals are in fact deeply corrupt, and driven by a thirst for money rather than idealistic purposes.

A frequent target of Ennis’ comic books production is organized religion, and “The Boys” is no exception. Going occasionally beyond the comic books, the TV series managed to offend Christians by using sexual profanity when referring to God, Jesus Christ, and the Virgin Mary. The show was attacked by arch-conservative Christians (not a particularly popular group with the media) and its producer decided to use their criticism as publicity, no doubt attracting a certain kind of audience.

Mainline religion is protected by its being mainline, which is not a reason to gratuitously offend it. It is much worse when religious minorities are attacked. “The Boys” TV series has a subplot involving something called Church of the Collective, a manipulative “cult” that manages to lure two of the superheroes. Eventually, the Church’s leader dies when his head explodes in an incident caused by a congresswoman, and former CIA agent’s, own superpowers.

Eric Kripke, who created the TV show, believes that the idea that their “primary motive is to take advantage of their followers” applies to “a lot of religions.” Organized religion, particularly Christianity, is constantly lampooned and exposed as corrupted and hypocritical in the show. God himself, if he exists, is accused of being a “mass murderer” and a con man, in a scene that some may regard as fun but can only be perceived as offensive by believers.

As for the Church of the Collective, Kripke publicly stated that any similarity between this fictional religion and the Church of Scientology “may be entirely coincidental and have nothing to do with satirizing (or condemning) the practices of Scientology.”

This statement notwithstanding, a quick Google search would lead to the conclusion that media have interpreted the Church of the Collective as a parody of Scientology. Those hostile to Scientology also used “The Boys” as a tool to promote a negative image of this new religion.

It would appear that the problem here lies with certain media, yet the scriptwriters, directors, and producers of “The Boys” are not entirely innocent. Just as they did with respect to Christian Evangelical large events with their fictional Believe Expo, with the Church of the Collective, they incorporated a number of anti-Scientology myths into story lines about a fictional religion. Those even only vaguely familiar with anti-Scientology literature would recognize it for what it is, and could easily view the hate speech against Scientology as vindicated and validated by a popular TV show.

Some may object that, unlike in other instances where hate speech has resulted in violence against religious minorities, nobody has been killed because of “The Boys.” Maybe, but in recent years there have been several violent incidents where members of the Church of Scientology have been attacked by individuals who had been persuaded by television shows and extreme websites that Scientology is an evil that should be stopped.

On January 3, 2019, a teenager broke into the premises of the Church of Scientology in Sydney, Australia, believing that his mother, who was participating in Church activities there, was in danger and had to be “rescued.” While he was being escorted out of the building, he stabbed a Scientologist to death, and seriously wounded another. There is little doubt that TV and web accounts of Scientology played a role in motivating the violent actions of this youth.

Terrorists who kill using as a pretext that they are protesting hate speech, such as those involved in the Charlie Hebdo-related murders, have no excuses. Yet, hate speech kills as well. It is not always possible to stop hate speech through courts of law, but at least we should see it for what it is: bigotry, not bravery, and a bigotry dangerous to us all.

Those who may object that it is “just a humorous parody” should consider this possible scenario. Imagine a movie or a novel that would use all the most disgusting myths propagated against Jews—their “greediness” as betrayed by their hooked nose, their constant conspiring against those not of their faith, and the fact that they even drink the blood of Christian babies—to portray an allegedly fictional religion, without using the name “Judaism.” Would we conclude that such fiction dangerously validates anti-Semitism, or just smile and regard it as fun?

Is this example merely hypothetical? Not really. Whatever the intentions of German musician Richard Wagner when he wrote “The Master-Singers of Nuremberg,” first represented in 1868, certainly in Nazi times the opera was represented to suggest that its villain, Beckmesser, was a Jew. Beckmesser’s Jewishness was subtly constructed trough stereotypes, although never explicitly mentioned.

While some believe Wagner was himself consciously propagating anti-Semitism through his opera (though others deny it), the Nazi representations of “The Master-Singers” are today unanimously condemned as quintessential examples of bigotry and hate speech. There is no reason why the same standard should not be used for bigotry harassing any religion today, be that religion large or small, well-known or misunderstood.

Source: Bitter Winter