Italy has recently seen the proposal of a law intended to punish mental manipulation, particularly ascribed to so-called “cults,” with prison sentences ranging from three to eight years. In an interview published by Bitter Winter, attorney Alessandro Amicarelli, chairman of Freedom of Belief (FOB), speaks with sociologist Massimo Introvigne, director of CESNUR, who raises serious concerns about the effectiveness and legitimacy of the proposed law. According to Introvigne, the bill is inspired by existing models in France and Spain, which have already proved problematic and difficult to implement. Many experts warn that such legislation risks introducing a vague and ideologically malleable offense that could endanger both religious freedom and freedom of expression.

A broader historical parallel is found in Freedom of Belief’s article “In memory of Aldo Braibanti,” which revisits the case of an Italian intellectual unjustly convicted of “plagio,” an outdated crime rooted in suspicion toward ideological independence.

Who Decides What Is “Absurd”?

One of the key points in the interview touches on the very definition of mental manipulation. Introvigne highlights the absence of an objective, universally accepted notion of the phenomenon, noting that judgments are often shaped by cultural bias. The interview draws attention to how even radical religious choices — such as those made by the nuns of Mother Teresa — have been accused of being the product of brainwashing. This prompts a broader reflection: do we really want judges deciding which doctrines are “normal” and which are “absurd”? (Such a scenario would be unthinkable, for instance, in the United States.) The bill risks targeting not only real cases of abuse, but also minority religious communities that operate lawfully and legitimately. A detailed analysis of these ideological distortions can be found in Freedom of Belief’s article “Anti-cult ideology and FECRIS: Dangers to religious freedom.”

Crimes Already Punishable and the Danger of Liberticidal Drift

Introvigne acknowledges the existence of actual abuses, such as those committed by the “Beasts of Satan” or exploitative self-styled gurus, but he points out that these crimes are already addressed by Italy’s penal code. Introducing a law focused on mental manipulation could paradoxically make it harder to prosecute these acts — drawing attention away from concrete accusations in favor of vague, ideologically loaded ones. The concern is that such a law may become a tool to target unpopular groups, enforcing justice selectively — tough on the weak, soft on the powerful — while eroding the principle of equal treatment under the law.

A Legislative Proposal Arising in a Climate of Religious and Cultural Hostility

The proposed law is far from neutral: it comes from the governing coalition and appears to reflect the demands of groups such as FECRIS (European Federation of Centres of Research and Information on Cults), which have long exhibited hostility toward religious freedom. FECRIS, while claiming neutrality, has played a controversial role in France, and maintains strong links with Russian networks where religious freedom is heavily curtailed, partly due to pressure from the Orthodox Church. Against this backdrop, the Italian proposal risks importing repressive legal models that undermine pluralism and cast suspicion over lawful religious expression.

A Flexible Concept of Secularism

This legislative initiative risks further eroding Italy’s already fragile secularism. On one hand, proponents are those who invoke state neutrality when targeting religious minorities; on the other, they argue the State must protect “our Catholic traditions,” effectively nullifying the very secular principles they claim to uphold. It is a contradiction that resurfaces repeatedly, despite the New Concordat of 1984 between Church and State having reaffirmed their mutual autonomy and the principle of laicity. In this atmosphere, the mental manipulation bill may serve less as a legal safeguard and more as an ideological device to reinforce Catholic cultural dominance in public life — perhaps, but maybe not, as we will see below.

A broader discussion on these dynamics is offered in Freedom of Belief’s article “Italy, the great Ramadan fear and the need for a mature laicity.”

A Double-Edged Weapon: The Law’s Crossfire Risk

As emphasised by Introvigne in the Bitter Winter interview, the risks of such a law go beyond its potential misuse against minority religions. Similar legislation in France, Belgium, and Spain has been leveraged by anti-cult associations to attack Catholic movements such as Opus Dei, the Legionaries of Christ, the Charismatic Renewal, and even the well-known Community of Sant’Egidio. The term “cult” lacks clarity and objectivity, and some fundamentalist Protestant groups regularly accuse Catholicism itself of being manipulative. This means that the proposed law could inadvertently strike against the principles and institutions that its political supporters seek to defend — making it a paradoxical tool that undermines its own unofficial goals.

A law of this kind, if approved, would not only risk reinforcing — directly or indirectly — confessional influences in Italy’s public sphere; it would also risk harming the Catholic Church itself. Its ambiguity could empower liberticidal actors hostile to religious freedom, transforming a fragile framework of secularism into a melting pot of incompatible ideologies and political agendas.

A Law Against “Mental Manipulation” in Italy: A Bad Idea

(Interview also published in Bitter Winter)

by Alessandro Amicarelli — A proposal would punish “mind control” allegedly practiced by “cults” with prison sentences ranging from three to eight years. An interview with Massimo Introvigne.

Massimo Introvigne (left) and Alessandro Amicarelli (right) at the recent conference ESSWE 10

A bill has been introduced in Italy that would punish “mental manipulation” (also known as brainwashing), allegedly used by so-called “cults” to recruit followers, with imprisonment of three to eight years. Is it true that most academic specialists on “cults” or new religious movements are opposed to this?

Yes, the vast majority. An appeal to this effect against a previous, very similar proposal, was signed by the most renowned Italian specialists and by the presidents or secretaries of the major international organizations that bring together sociologists and historians of religions. The same happened when the French law of 2001 (revised and further worsened in 2024) was approved, on which the legislation proposed in Italy is in many ways based. Of course, there are also scholars in the international academic world who hold different positions, but they are a tiny minority among the specialists of new religious movements.

Why should we believe academic scholars and not the “victims of cults,” who are making themselves heard in support of the bill?

For five good reasons. (1) The so-called “cults” function like revolving doors: many enter, but many leave. There are millions of former members of controversial religious movements. The hundreds or even thousands who protest are therefore not a representative sample. Scholarly studies show that even in the most contentious groups, over 85% of former members do not take a militant stance against the movement they left, but simply return to ordinary social life, acknowledging both positive and negative aspects of their experience when interviewed. (2) The sample of those who protest is self-selected: it is only they, and not the vast majority of former members who hold different positions, who make themselves heard, send emails, and contact parliamentarians. (3) Worse still, the sample is selected by “anti-cult” associations that have their agenda, which is prejudicially hostile to groups they define as “cults.” (4) No one would form an opinion of the Catholic Church by listening only to former priests who have left the priesthood or to the minority of former priests who protest against the Church, because even in this case many simply return to social life without taking up militant attitudes; or of a divorced public figure by trusting only the opinion of his ex-spouse. (5) Even in cases—which certainly exist—where the “victims” report real abuses, it is not necessarily true that their opinions on how to combat them are more authoritative than those of experts with the necessary professional skills. A victim of terrorism certainly deserves sympathy and can faithfully describe their suffering, but they are not necessarily authoritative when proposing anti-terrorism measures.

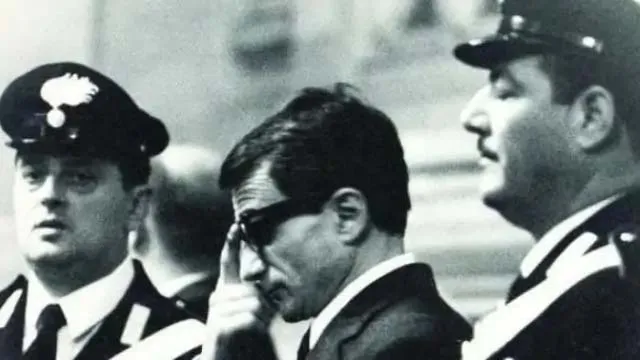

So, you admit the existence of real abuse and violence, from providers of occult services who rape their clients to the homicides of the Italian group known as the Beasts of Satan? And in the face of such horrors, how can one not be in favor of a law against cults and mental manipulation?

I indeed admit that abuse exists. In the case of the Beasts of Satan or magicians-cum-sexual predators, we are dealing with obvious crimes, already provided for and punished by the Criminal Code: murder, violence, rape, and so on. The courts have convicted those responsible without the need for a law on mental manipulation. Indeed, it would have been much more difficult to convict the Beasts of Satan or this or that violent or fraudulent occult services provider on a vague charge of “mental manipulation” than for very concrete and specific crimes such as murder or rape. The situation in Italy is similar to that in Germany and Switzerland, where there is no law against mental manipulation. On the contrary, commissions appointed by parliaments have recommended against adopting such a law, yet occult practitioners and religionists who have committed common crimes have received severe sentences.

The “Beasts of Satan.” From X

If experience shows that these laws are difficult to enforce, why do you say at the same time that they are dangerous for religious freedom?

Laws that create vaguely defined crimes that skilled lawyers and experts can endlessly argue about are loose cannons at the mercy of the prevailing cultural climate. They can be used against any unpopular group. They are often strong with the weak and weak with the strong. They have been applied against tiny groups that cannot afford good lawyers in Spain and France. In contrast, millionaire leaders and groups that might have been guilty but were better defended have escaped prosecution.

But “cults” are not religions… Why are you talking about religious freedom?

The notion of “cult,” or “secte” in French and similar words derived from the Latin “secta” in other languages (to be translated into English as “cults” rather than as “sects”), originated in the sociology of religion to identify religious groups where the majority of members were not born into it but joined as adults. According to the sociologists who first used this notion of “cult” in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, early Christianity was a “cult,” which then became a “church” after a couple of centuries, when it started having a majority of members who had been born in the faith. As can be seen, the notion did not imply any negative value judgment. Today, this is no longer the case. “Cult” is commonly understood to mean a “dangerous” group. But the notion is ambiguous. A “dangerous cult” can be understood as a group that commits crimes under common law (murder, rape, violence). Or it can be said that a “cult” is a group that spreads ideas and practices so absurd that only through “mental manipulation” can anyone be convinced to join. This is where the danger to religious freedom arises, because what ideas are “absurd” can be assessed differently depending on the ideological prejudices of the person judging. On what basis is a “cult” considered harmful to its followers? For a secular humanist, the act of Mother Teresa (1910–1997) risking her life to care for a terminally ill, infectious patient in India, who will die anyway, is absurd. There was no shortage of literature at the time accusing Mother Teresa of “brainwashing.” How else could she have convinced good middle-class girls from New York or Rome to go and clean the sores of terminally ill people on the streets of Kolkata? In truth, the distinction between “cults” and “religions” (or between “true” religions and “pseudo-religions”) is entirely subjective. The Catholic Church is often accused of being a “cult” by fundamentalist Protestant groups… and vice versa.

Nuns of Mother Theresa’s order, the Missionaries of Charity. Credits

But not everyone is Mother Teresa. Isn’t it true that some claim divine powers to extort millions from their followers or abuse them?

Here, a rigorous distinction is needed, one that goes to the heart of freedom of religion or belief. If some beat, kill, or rape people, they cannot hide behind the shield of religious freedom to escape the proper application of laws on common crimes. These laws already exist. Those who want to introduce the crime of mental manipulation wish to target those who do not beat, rape, or kill anyone but induce their followers to believe in doctrines that the promoters of the law consider so absurd that they can only be embraced as a result of “mental manipulation.” Followers will donate large sums of money, much of their time, or perhaps their entire lives to promote these doctrines, as others do for socially approved beliefs. Those who were professionals or students until yesterday will lead monastic or missionary lives in great hardship tomorrow. The problem is how to decide which of these choices are “absurd”—and therefore explainable only by “mental manipulation”—and which are “normal.” Many would agree that the choice of Mother Teresa’s nuns is acceptable and even sublime, and that of those who go to live in India as missionaries for a holy man accused of pedophilia is “absurd.” But not everyone would agree. Mother Teresa, as we have seen, was accused of “brainwashing,” and the guru has his defenders who claim that he is unjustly slandered. Do we want to turn judges into theologians and let them decide which doctrines are “absurd” and which are “normal”?

However, the proposed law does not deal with doctrines. It only condemns practices of mental manipulation…

In theory. In practice, which choices are “free” and which result from “mental manipulation” cannot be assessed a priori, but only a posteriori by examining the options themselves. If the choice is deemed acceptable by those called upon to judge, it will be considered free; if it is considered unacceptable, it will be said to result from “mental manipulation” because no one would freely accept specific “absurd” ideas or practices.

But is there no objective notion of “mental manipulation” that can be defined independently of doctrines?

No. The issue of “mental manipulation” arose historically from a problem faced by German scholars, many of whom were Marxists, at the time of the Nazi rise to power. How was it possible that not only the bourgeoisie, as their somewhat rigid Marxism would have predicted, but also many “proletarians” became Nazis? Using the nascent psychoanalysis and combining it with some elements of Marxist cultural criticism, some responded that the “proletarians” did not become Nazis freely but were victims of “mental manipulation” by the “pied pipers” of Nazism. After the war, many of these German scholars had moved to the US, and the same theory was applied to Communism. Communism, it was said, is such an absurd doctrine that no one could embrace it freely; those who do are victims of techniques invented in Russia and China of “brainwashing,” an expression coined in 1950 by CIA agent Edward Hunter (1902–1978). Towards the end of the Cold War, the theme of “brainwashing” was taken up by psychiatrists and psychologists hostile to religion to attack religious fervor in general: the first attacks were directed against evangelical Protestants and Catholics by the secular British psychiatrist William W. Sargant (1907–1988). Here, too, the pattern was the same: in the modern world, specific religious ideas are so “absurd” that adherence to them can only be explained by “brainwashing.” Later, realizing that attacking religion in general was too broad a target, it was mainly the controversial American psychologist Margaret T. Singer (1921–2003) who narrowed its application to “cults.” But the circular reasoning remained: which groups are “cults”? Those who practice “brainwashing.” How do we know they practice “brainwashing”? Because they are “cults,” i.e., their ideas and practices are so bizarre that they cannot be explained by free adherence.

William W. Sargant. Credits

But don’t these theories have their respected place in academic literature?

Let us distinguish. The crude version, which supported the CIA’s anti-communist propaganda in the 1950s, certainly does not belong in the world of science. Today, no one would use the phonograph example, as the then CIA director Allen Welsh Dulles (1893–1969) did in 1953: there is a record in the brain and Communists have learned to remove and change it. The more sophisticated version—linked to names such as Robert Lifton and Edgar Schein—can be appreciated differently depending on views on the psychoanalytic theories it largely derives from. In any case, this more scholarly version does not claim that “mental manipulation” works in a “magical” or automatic way, nor that it can be “isolated” regardless of the doctrines it serves. In short, the most “respectable” version of the manipulation theory cannot be used to define crimes. The law must be general, and this version argues that each case is unique and requires an examination of the context and doctrines. In reality, as in French law, the ideological framework underlying the Italian proposal is still the naive “CIA” view that isolating the form from the content of manipulation is possible. However, scholars of new religious movements have thoroughly discredited this theoretical approach.

Honest religious movements, including Catholic ones, have nothing to fear from the proposed law, right?

Wrong. It all depends on who reports and who judges. For some, especially in a particular cultural climate where religious conflicts and aggressive secularism are on the rise, even the choice to devote one’s life, or to donate large sums of money, to a Catholic, Protestant, or Buddhist organization deemed excessively “strict” for the prevailing cultural climate may appear “absurd” and necessarily imply mental manipulation. Foreign experience teaches us that groups such as Opus Dei have been among those accused in France and Spain of practicing “mental manipulation” by anti-cult movements. In Argentina, the same prosecutors who prosecute “cults” have taken action against Opus Dei, which has even been accused of human trafficking. Catholic movements are by no means safe. In Italy, in our collective memory, the 1981 Constitutional Court ruling that eliminated the crime of “plagio” (the Italian version of “brainwashing”) is linked to the case of the communist homosexual philosopher Aldo Braibanti (1922–2014). But in reality, the ruling did not intervene in the Braibanti case, but in that of the Catholic priest Father Emilio Grasso, accused by some parents of “brainwashing” their children to initiate them into the service of the poorest of the poor in the slums. To some, this kind of Catholic fervor could and can appear “absurd,” a typical result of “mental manipulation.”

Aldo Braibanti (1922-2014) was the only person found guilty of “plagio” with a final decision in Italian legal history. From X

But did the 1981 Constitutional Court ruling abolishing brainwashing not leave a legislative vacuum?

Who knows how we survived a legislative vacuum that lasted over forty years! No: the 1981 ruling—just read it—did not criticize the legislation on “plagio” by calling on Parliament to pass another one, but argued that “plagio,” as it was understood then and is understood today by supporters of the bill, is an imaginary crime, a ploy to outlaw unpopular or unwelcome ideas. Unable, for obvious constitutional reasons, to attack ideas, it is claimed that such strange ideas can only gain support through “plagio” or “mental manipulation.” It is said that these techniques, not the ideas, are to be criminalized. However, the Constitutional Court understood well in 1981 that this was, in fact, a subtle way of criminalizing ideas. Its arguments remain valid today and should prompt anyone who cares about freedom to oppose any attempt to reintroduce “plagio,” by any other name, into our legislation.