The secular nature of Pakistan came immediately under attack by political Islam. 2,000 Ahmadis were slaughtered in the riots, until martial law was imposed.

Article 2 of 5. Read article 1.

by Massimo Introvigne — Because of the theological peculiarities discussed in the first article of the series, the Ahmadis were regarded as heretics by the other Muslims and persecuted since their foundation. Their bloodiest persecution was, however, a consequence of the foundation of Pakistan as a state for the Muslims of former British India.

The persecution of religious minorities should not have happened, and was not part of the original project of Muhammad Ali Jinnah, the father of modern Pakistan. When he was elected President of the Constituent Assembly in 1947, Jinnah promised to the citizens of Pakistan: “You are free; you are free to go to your temples; you are free to go to your mosques or to any other places of worship in this state of Pakistan. You may belong to any religion or caste or creed—that has nothing to do with the business of the state…. We are starting in the days when there is no discrimination, no distinction between one community and another, no discrimination between one caste or creed and another. We are starting with this fundamental principle that we are all citizens and equal citizens of one state.” In fact, Jinnah appointed an Ahmadi, Muhammad Zafarullah Khan, as Pakistan’s first Foreign Minister.

However, Jinnah’s project was opposed by conservative and traditionalist Islamic groups, including Jamaat-e-Islami, the oldest fundamentalist Muslim movement in the world, whose founder Abul A’la Maududi explicitly stated that he would oppose any political system in Pakistan that would grant religious liberty to the heretic Ahmadis.

Abul A’la Maududi. From Twitter.

A party representing political Islam, Majlis-e Ahrar-e Islam, had been founded in Lahore in 1929. Although divided in two branches by internecine struggles, it emerged as a significant force after the 1947 Partition of India and the creation of Pakistan. A key item in its agenda was that religious freedom should be denied to the Ahmadis.

Majlis-e Ahrar-e Islam gathered other Islamic parties in an anti-Ahmadi coalition, which on January 21, 1953, presented an ultimatum to the government, which was led after the death of Jinnah in 1948 by the less charismatic Khwaja Nazimuddin. At that time, Pakistan still consisted of the two non-contiguous areas of West Pakistan (present-day Pakistan) and East Pakistan (present-day Bangladesh). Nazimuddin was a Bengali who came from East Pakistan, which made him less popular in West Pakistan.

The ultimatum asked for the removal of Zafarullah Khan from his position as Foreign Minister, the removal of all other Ahmadis from top government positions, and an official declaration that Ahmadis were not Muslims. If the ultimatum was rejected, Majlis-e Ahrar-e Islam and its allies threatened armed revolt.

Muhammad Zafarullah Khan (second from the left, front row) visiting Japan and meeting with Japanese Ahmadis (credits).

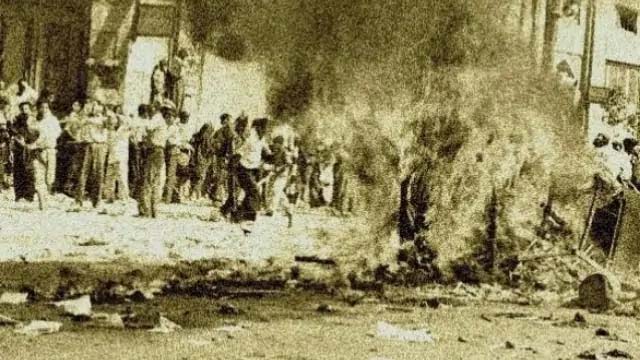

At the date of its expiration, February 22, 1953, the ultimatum had not received any answer from the government, and on February 23 riots started throughout the country, targeting Ahmadis and their places of worship. The number of Ahmadis killed is disputed, with most historians believing they were around 2,000, some of them tortured to death and others burned alive.

The anti-Ahmadis Lahore riots of 1953. From Twitter.

The reaction of the Nazimuddin government was hesitant, failed to effectively protect the Ahmadis, and mostly consisted in prohibiting Ahmadi newspapers from publishing details of the persecution, lest it might generate international reactions. However, until 1956, Pakistan had a Governor General representing the British Crown, with extensive powers. Governor General Malik Ghulam Muhammad on March 6 handed over the administration of Lahore, where the worst riots were occurring, to the military, and imposed martial law.

The military repressed the riots, and arrested Maududi and Muslim politician Abdul Sattar Khan Niazi. They were sentenced to death, although the sentence was commuted to life imprisonment, and they ended up spending in jail a short period of time only. 11 rioters and 4 military perished in the fights. The Governor General used the prerogatives granted to him and dismissed Prime Minister Nazimuddin, calling the Pakistani Ambassador to the United Nations Muhammad Ali Bogra to replace him, and the entire cabinet.

The Governor also called for an investigation of the riots, which after one year of work produced the Munir Report of 1954, named after the Supreme Court justice (later its Chief Justice) Muhammad Munir who chaired the commission. The report defended the religious liberty of the Ahmadis, and led to the ban of the party Majlis-e Ahrar-e Islam.

However, political Islam remained a force to be reckoned with in Pakistan, and played a crucial role in the drafting of the 1956 Constitution, which was opposed by all religious minorities. Article 198 mandated that all laws opposed to Islam should be considered unconstitutional and “existing laws shall be brought into conformity” with the principles of Islam. Pakistan became an Islamic Republic, and the umbilical tie with the United Kingdom was rescinded.

The new Constitution immediately created political instability, which led to the military coup of 1958. Although Ahmadis were never really free from harassment, military rule prevented the bloodiest riots. As we will see in the next article, the situation changed from the worse when “Islamic socialist” Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto rose to prominence in the 1970s.

Source: Bitter Winter