In this series of articles, Rosita Šorytė will examine two examples of “New Age anti-cultism” pertinent to AROPL. She will also explore whether New Age anti-cultism will be recognized as a legitimate component of the global anti-cult movement and whether it will benefit from the efforts of its coordinating agencies.

Rosita Šorytė, member of FOB’ Scientific Committee, joined in 1992 the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Lithuania, and worked for 25 years as a diplomat, inter alia at the UNESCO in Paris and the United Nations in New York. In 2011, she served as the representative of the Lithuanian Chairmanship of the OSCE (Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe) at the Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (Warsaw). In 2012-2013, she chaired the European Union Working Group on Humanitarian Aid on behalf of the Lithuanian pro tempore presidency of the European Union. She takes a special interest in religious liberty and on refugees escaping their countries due to religious persecution, and is co-founder and President of ORLIR, the International Observatory of Religious Liberty of Refugees. She is also the author of several articles on religious liberty and religion-based humanitarian initiatives.

AROPL and the Rise of New Age Anti-Cultism 1. The Anti-Cult Movement

The opposition to “cults” has so far consisted of two main sides: religious and secular. A third side is emerging, targeting the Ahmadi Religion of Peace and Light.

Article 1 of 5. Read article 2, article 3, article 4 and article 5

by Rosita Šorytė — In July 2025, many members of the Ahmadi Religion of Peace and Light (AROPL) became aware of an organized anti-cult movement when several British media outlets, starting with “The Guardian,” launched attacks against them. The campaign employed typical arguments used to criticize groups labeled as “cults.” The origin of these attacks can be traced back to a slanderous article by Be Scofield on her blog, “GuruMag.”

A sensationalist anti-AROPL article in “The Guardian” based on the revelations of “New Age anti-cultist” Be Scofield.

Scholars of new religious movements have studied the anti-cult movement for decades. Researchers describe it as comprising two distinct sub-groups. Massimo Introvigne referred to the first of these in a well-known 1993 article as the “counter-cult movement,” which is driven by religious groups that feel threatened by the competition posed by new arrivals in the competitive religious market. These groups often label the new movements as illegitimate, heretical, and even demonic.

In some countries, religious counter-cultists can mobilize the government against groups they label as “cults.” In Iran, the anti-cult movement is intertwined with the theocratic government. Countries like Pakistan and Malaysia have official Islamic councils that identify which groups they consider heretical “cults,” and these designations often lead to governmental repression. In Israel, as documented by Willy Fautré, Jewish ultra-Orthodox anti-cultism can influence governments that rely on support from religious parties.

Although Russia is theoretically a secular state, the Putin regime seeks the support of the Russian Orthodox Church, which plays a significant role in establishing a unified consensus. In return for this support, the regime takes action against groups like the Jehovah’s Witnesses, which the Russian Orthodox Church condemns as “sheep-stealers” and “cults.” In South Korea, the anti-cult movement is primarily organized by Protestant fundamentalists. Despite not representing the majority of the population, they can exert considerable influence over political parties, elections, and government actions by voting together as a bloc.

An event organized in Frankfurt by the World Association Against Heresy, a Protestant fundamentalist South Korean anti-cult association that often cooperates with China. From Weibo.

The second subgroup of the anti-cult movement is secular. It emerged from left-wing activists and intellectuals concerned about the rise of conservative religion and from parents of students who, in the late 20th century, decided to leave college to become full-time missionaries, monks, or nuns for new religious movements. These parents, who were often non-religious, were less concerned about the theological orthodoxy of these new movements. Their primary concern was to “get their children back,” and they listened intently to psychologists who claimed that their children had been “brainwashed.”

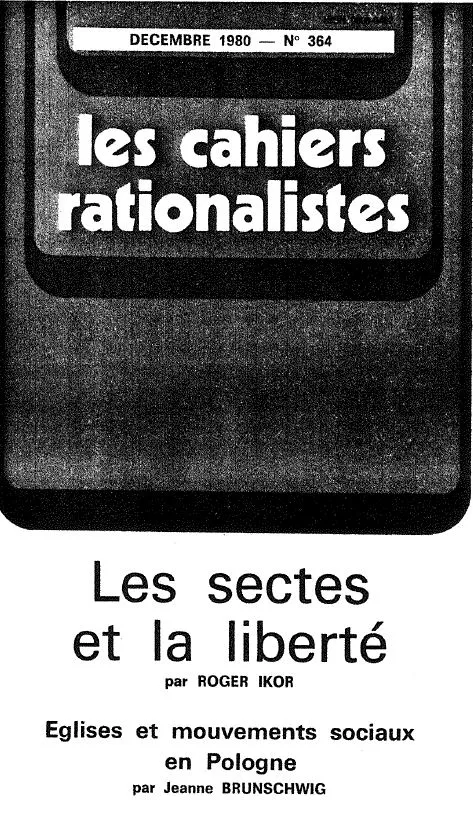

Some of the fathers of the anti-cult movements, particularly in secular France, admitted they were against all religions and used “cults” as a starting point for a broader anti-religious campaign. Roger Ikor (1912–1986), the founder of the French anti-cult organization CCMM, stated, “There isn’t between a cult and a religion a difference of nature, or rather of principle; there is only a difference of degree and dimensions… If it were up to us, we would put an end to all this nonsense, that of cults, but also that of large religions.” He also referenced “Muhammad, Christ, and Moses” as predecessors of today’s “cult” leaders (“Les sectes et la liberté,” “Les Cahiers rationalistes” 364, 1980, pp. 76 and 87).

The issue of “Les Cahiers rationalistes” with Ikor’s article “Les sectes et la liberté.”

In a book published a few days ago, one of the international anti-cult movement’s leading ideologists, Canadian sociologist Stephen Kent, argues that, together with “cult” leaders, figures such as the Biblical Prophet Ezekiel, Paul the Apostle, and Muhammad were all either schizophrenic or epileptic. More broadly, Kent insists that “There is clinical reason to assume that people who believe that they are having extraterrestrial contact may be demonstrating a symptom of schizophrenia.” As for “people who maintain that non-material spirits and forces do exist” and “offer prayers for divine intercession,” the fact that they harbor “magical” beliefs indicates that they may suffer from “mental disorders.” “A good number of religions,” including the largest ones, “were founded by mentally disordered minds,” he concludes (“Psychobiographies and Godly Visions: Disordered Minds and the Origins of Religiosity,” Palgrave Macmillan, 2025, pp. 64, 60, 258).

China is home to the largest anti-cult organization in the world, the China Anti-Xie-Jiao Association, which is promoted and controlled by the Chinese Communist Party through the United Front. Most of its leaders are strong advocates of “scientific atheism” and Marxist dialectical materialism, and they maintain a hostile stance toward all religions.

The sectarian counter-cult movement and the secular anti-cult movement are distinct but interconnected. Their ideologies differ, and there is always a risk that secular anti-cultists may target the religious organizations of counter-cultists. Nevertheless, operating under the principle that “the enemy of my enemy is my friend,” these groups have found ways to collaborate.

In Japan and South Korea, we have witnessed a troubling alliance between fundamentalist and theoretically anti-Communist Christian pastors—who also act as deprogrammers—, left-wing activists and lawyers, and even Chinese intelligence services, as established by court rulings. Similarly, in Israel, ultra-Orthodox Jews readily cooperate with atheist anti-religious organizations to denounce “cults” and advocate for laws against them.

FECRIS, the umbrella organization funded by French taxpayers that coordinates anti-cult movements across Europe and beyond, includes both deeply secular movements, such as the one founded by Ikor, and until 2023 (when it was forced to exclude it due to the Ukrainian war ) the anti-cult agency of the Russian Orthodox Church, whose leaders are employees of the Moscow Patriarchate. Furthermore, books written by Western secular anti-cultists are translated into Farsi and used by the ayatollah regime in Iran against “cults” (see Sajjad Adeliyan Tous and James T. Richardson, “Managing Religion and Religious Changes in Iran: A Socio-Legal Analysis,” Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2024, p. 30).

The recent assault on the AROPL has uncovered the presence of a relatively new third player that warrants attention. I will refer to it as “New Age anti-cultism.” This movement does not oppose so-called “cults” in the name of secular humanism or mainstream religion; instead, it critiques “cultic” beliefs based on a confusing blend of astrology, energy theories, and popular esotericism.

Although other instances exist, I will examine two examples pertinent to AROPL in this series. Additionally, I will explore whether New Age anti-cultism will be recognized as a legitimate component of the global anti-cult movement and whether it will benefit from the efforts of its coordinating agencies.

Source: Bitter Winter