"We are scholars, human rights activists, reporters. and lawyers, all with a substantial experience in the field of new religious movements (derogatorily called “cults” by their opponents). Some of us have studied the Korean Christian new religious movement known as Shincheonji Church of Jesus, the Temple of the Tabernacle of the Testimony (in short, Shincheonji).

We are concerned with the vast amount of inaccurate information circulating about Shincheonji and its involvement in the coronavirus crisis in South Korea. We have interviewed members of Shincheonji and Korean scholars, and examined documents from both the South Korean government and Shincheonji. We have prepared this white paper to help international organizations, the media and other concerned parties to better understand the situation. None of us is a member of Shincheonji, nor do we adhere to its theology. But theological criticism should not be confused with discrimination or violation of human rights.

Massimo Introvigne, Center for Studies on New Religions

Willy Fautré, Human Rights Without Frontiers

Rosita Šorytė, International Observatory of Human Rights of Refugees

Alessandro Amicarelli, attorney, European Federation for Freedom of Belief

Marco Respinti, journalist

Shincheonji and Coronavirus in South Korea:

Sorting Fact from Fiction

A White Paper

Massimo Introvigne is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. He is the author of more than 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015, he served as the chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Massimo Introvigne is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. He is the author of more than 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015, he served as the chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Willy Fautré, former chargé de mission at the Cabinet of the Belgian Ministry of Education and at the Belgian Parliament, is the director of Human Rights Without Frontiers, an NGO based in Brussels that he founded in 1988. He has carried out fact-finding missions on human rights and religious freedom in more than 25 countries. He is a lecturer in universities in the fields of religious freedom and human rights. He has published many articles in academic journals about the relations between state and religions. He regularly organizes conferences at the European Parliament, including freedom of religion or belief. For years, he has developed religious freedom advocacy in European institutions, at the OSCE, and at the UN.

Willy Fautré, former chargé de mission at the Cabinet of the Belgian Ministry of Education and at the Belgian Parliament, is the director of Human Rights Without Frontiers, an NGO based in Brussels that he founded in 1988. He has carried out fact-finding missions on human rights and religious freedom in more than 25 countries. He is a lecturer in universities in the fields of religious freedom and human rights. He has published many articles in academic journals about the relations between state and religions. He regularly organizes conferences at the European Parliament, including freedom of religion or belief. For years, he has developed religious freedom advocacy in European institutions, at the OSCE, and at the UN.

Rosita Šorytė joined in 1992 the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Lithuania, and worked for 25 years as a diplomat, inter alia at the UNESCO in Paris and the United Nations in New York. In 2011, she served as the representative of the Lithuanian Chairmanship of the OSCE (Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe) at the Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (Warsaw). In 2012-2013, she chaired the European Union Working Group on Humanitarian Aid on behalf of the Lithuanian pro tempore presidency of the European Union. She takes a special interest in religious liberty and on refugees escaping their countries due to religious persecution, and is co-founder and President of ORLIR, the International Observatory of Religious Liberty of Refugees. She is also the author of several articles on religious liberty and religion-based humanitarian initiatives.

Rosita Šorytė joined in 1992 the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Lithuania, and worked for 25 years as a diplomat, inter alia at the UNESCO in Paris and the United Nations in New York. In 2011, she served as the representative of the Lithuanian Chairmanship of the OSCE (Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe) at the Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (Warsaw). In 2012-2013, she chaired the European Union Working Group on Humanitarian Aid on behalf of the Lithuanian pro tempore presidency of the European Union. She takes a special interest in religious liberty and on refugees escaping their countries due to religious persecution, and is co-founder and President of ORLIR, the International Observatory of Religious Liberty of Refugees. She is also the author of several articles on religious liberty and religion-based humanitarian initiatives.

Alessandro Amicarelli is a member and director of Obaseki Solicitors Law Firm in London. He is a solicitor of the Senior Courts of England and Wales, and a barrister of Italy, specializing in International and Human Rights Law and Immigration and Refugee Law. He has lectured extensively on human rights, and taught courses inter alia at Carlo Bo University in Urbino, Italy, and Soochow University in Taipei, Taiwan (ROC). He is the current chairman and spokesperson of the European Federation for Freedom of Belief (FOB).

Alessandro Amicarelli is a member and director of Obaseki Solicitors Law Firm in London. He is a solicitor of the Senior Courts of England and Wales, and a barrister of Italy, specializing in International and Human Rights Law and Immigration and Refugee Law. He has lectured extensively on human rights, and taught courses inter alia at Carlo Bo University in Urbino, Italy, and Soochow University in Taipei, Taiwan (ROC). He is the current chairman and spokesperson of the European Federation for Freedom of Belief (FOB).

Marco Respinti is an Italian professional journalist, essayist, translator, and lecturer. He has contributed and contributes to several journals and magazines both in print and online, in Italy and abroad. One of his books, published in 2008, concerns human rights in China. A Senior fellow at the Russell Kirk Center for Cultural Renewal, a non-partisan, non-profit U.S. educational organization based in Mecosta, Michigan, he is also a founding member as well as Board member of the Center for European Renewal, a non-profit, non-partisan pan-European educational organization based in The Hague, The Netherlands.

Marco Respinti is an Italian professional journalist, essayist, translator, and lecturer. He has contributed and contributes to several journals and magazines both in print and online, in Italy and abroad. One of his books, published in 2008, concerns human rights in China. A Senior fellow at the Russell Kirk Center for Cultural Renewal, a non-partisan, non-profit U.S. educational organization based in Mecosta, Michigan, he is also a founding member as well as Board member of the Center for European Renewal, a non-profit, non-partisan pan-European educational organization based in The Hague, The Netherlands.

1. Introduction: Epidemics and Religions

We are scholars, human rights activists, reporters, and lawyers, all with a substantial experience in the field of new religious movements (derogatorily called “cults” by their opponents). Some of us have studied the Korean Christian new religious movement known as Shincheonji Church of Jesus, the Temple of the Tabernacle of the Testimony (in short, Shincheonji).

We are concerned with the vast amount of inaccurate information circulating about Shincheonji and its involvement in the coronavirus crisis in South Korea. We have interviewed members of Shincheonji and Korean scholars, and examined documents from both the South Korean government and Shincheonji. We have prepared this white paper to help international organizations, the media and other concerned parties to better understand the situation. None of us is a member of Shincheonji, nor do we adhere to its theology. But theological criticism should not be confused with discrimination or violation of human rights.

Looking for scapegoats is historically common in times of epidemics. Often, these scapegoats are identified with unpopular religious minorities. During the Black Death epidemics of the 14th century in Europe, Jews were accused of intentionally spreading the plague out of their alleged hatred for the Christian majority. Thousands were lynched or burned at stake. In the city of Strasbourg, France, only, on February 14, 1349, 2,000 Jews were burned for their supposed plague-spreading crimes (Gottlieb 1983, 74).

In 1545, during the rule of John Calvin (1509–1564) in Geneva, religious dissidents were blamed for an outbreak of the plague, and at least 29 were executed (Naphy 2003, 90–1). Catholics in Protestant countries and Protestants in Catholic countries continued to be executed in the 16th and 17th century under accusation of plague-spreading (Naphy 2002). As late as 1630 in Milan, practitioners of forms of folk religion easily mistaken for witchcraft were accused of spreading the plague and executed (Nicolini 1937)—a story well-known in Italy as it was mentioned in the country’s national novel, The Betrothed by Alessandro Manzoni (1785–1873).

FACT

- Religious gatherings in time of epidemics may contribute to spreading viruses.

FICTION

- It is not true that religious minorities willingly spread viruses and cause epidemics out of their hatred for the majority.

- It is of course true that religious gatherings, pilgrimages, and processions may be dangerous in times of epidemics, as all other mass events, and may contribute to spreading viruses. However, accusations that certain religious minorities willingly spread epidemics because they hate the majority have been unanimously exposed by historians as conspiracy theories, moral panics, and pretexts for persecuting unpopular groups.

2. What Is Shincheonji?

When news about Shincheonji and the virus started circulating outside of South Korea, most international media took their information about this Korean movement from low-level Internet sources and from Korean media that, for reasons explained in the next session, have a long tradition of hostility against Shincheonji. As a result, false information spread from one article to another.

Korea is home to hundreds of new religious movements (NRMs), both Christian and non-Christian. In the 1960s, the most successful Christian NRM in South Korea was the Olive Tree, founded by Park Tae-seon (1915–1990), credited with 1.5 million followers. Park’s claim to be God incarnate, with a position higher than Jesus Christ, led many to leave the Olive Tree. Some joined a different NRM known as the Tabernacle Temple. The latter was born in 1966 from the experience of eight persons (seven “messengers” and one elder), who gathered on the Cheonggye Mountain, where they remained for 100 days, feeling they were learning the Bible guided by the Holy Spirit.

Lee Man-Hee, born on September 15, 1931, at Punggak Village, Cheongdo District, North Gyeongsang Province, Korea (now South Korea), a self-taught evangelist and former military man, joined the Olive Tree in 1957 and the Tabernacle Temple in 1967. When corruption developed in the Tabernacle Temple, leading to the arrest of its leader, Yoo Jae Yul (b. 1949), Lee, giving voice to many of its members, called for reform. The Temple leadership reacted by having him threatened and beaten, and Lee left to establish his own church, Shincheonji (a name meaning “New Heaven and New Earth”) Church of Jesus, the Temple of the Tabernacle of the Testimony, which was founded on March 14, 1984. Meanwhile, the Tabernacle Temple had collapsed and merged with one branch of the Presbyterian Church. Shincheonji believes that, while the old Tabernacle collapsed, a new Tabernacle of the Testimony came into being.

According to Lee, all these events were predicted in the Book of Revelation of the Bible, whose prophecies were realized in South Korea through the rise and destruction of the Tabernacle Temple, opening the way for the emergence of the “one who overcomes,” the “promised pastor” announced in the New Testament.

Shincheonji believes that this promised pastor is Lee himself.

Contrary to what several media reported in the present crisis, Shincheonji does not regard Lee (whom they call Chairman Lee) as God or the second coming of Jesus Christ. As the promised pastor, he is at the center of the covenant between God and humanity, the New Spiritual Israel, after the Physical Israel of the Old Testament and the Spiritual Israel inaugurated by Jesus. After the true Christian doctrine had been progressively corrupted by both the Catholic and the Protestant churches, the promised pastor, i.e. Lee, was called to restore it in its original purity and to fulfill the covenant established by Jesus 2,000 years ago. But for Shincheonji Chairman Lee is a human being, not a divine incarnation, although one entrusted by God with a very special and important mission.

As other Christian millenarian movements, Shincheonji believes that we will soon enter in the Millennium announced in the Book of Revelation, an era of peace that will last for 1,000 years. Both the 144,000 saints mentioned in the Book of Revelation and a larger “great white multitude” will live through the Millennium. Many members of Shincheonji believe that Chairman Lee will live to see the inauguration of the Millennium. To the objection that this seems unlikely, since Lee will turn 90 in 2021, they answer that they maintain their trust in God’s love and promises.

Shincheonji is divided into twelve tribes, which manage the church in different areas of Korea and are also in charge of missions abroad. Services are offered twice a week, on Wednesday and Sunday. Shincheonji members kneel during the services, therefore, there are no chairs (except for the elderly and infirm) in their churches. Churches are often located in large buildings where other floors serve different purposes. This happens both because securing government permission for Shincheonji places of worship is difficult, and land prices in some metropolitan areas are very high and exceed the financial possibilities of the local congregations.

Shincheonji’s growth was slow initially, but accelerated from the 1990s on. By 2007, membership had reached 45,000. There were 120,000 members in 2012, 140,000 in 2014, 170,000 in 2016, and 200,000 in 2018, with an expansion to all continents, although most members continue to reside in South Korea.

Unlike other millenarian movements, which simply wait for God to bring us into the Millennium, Shincheonji believes that God wants humans to cooperate in its preparation, through good humanitarian deeds and the promotion of peace. Chairman Lee has promoted an impressive number of initiatives for peace education, international cooperation, and humanitarian and charitable aid, most of them under the aegis of HWPL (Heavenly Culture, World Peace, Restoration of Light), an organization he founded in 2013. While opponents object that HWPL is just a front to recruit new members for Shincheonji, this appears as highly unlikely. Presidents and prime ministers, international organizations dignitaries, and leaders of different religions participate in HWPL initiatives. While it is correct to say that they increase the visibility of Chairman Lee as a global religious and humanitarian leader, obviously Shincheonji does not expect that these international luminaries will convert to its faith (for more on Shincheonji, see Introvigne 2019).

FACT

- Shincheonji believes that it represents the New Spiritual Israel, restoring the original message of Jesus Christ that both Catholics and Protestants had corrupted.

- Shincheonji believes that Lee Man Hee is the “promised pastor” chosen by God to lead humanity into the Millennium.

- Shincheonji believes that the Millennium, a kingdom of peace that will last 1,000 years, is imminent, and that both 144,000 “saints” and a larger “great white multitude” will enter the Millennial kingdom.

- Most members of Shincheonji believe that Chairman Lee will live to see the advent of the Millennium.

- Chairman Lee teaches that humans should actively cooperate with God to create a kingdom of peace, and promotes peace education and humanitarian initiatives through an organization called HWPL (Heavenly Culture, World Peace, Restoration of Light).

FICTION

- It is not true that Shincheonji regards Chairman Lee as God or as a new incarnation of Jesus Christ.

- It is not true that Shincheonji teaches that only 144,000 members of Shincheonji will enter the Millennium.

- It is not true that HWPL’s function is to serve as a front to recruit new members for Shincheonji.

3. Why Is There A Strong Opposition to Shincheonji?

While in other countries, arch-conservative and fundamentalist brands of Protestantism represent a minority among the Protestants, for historical reasons connected to early missions to Korea, and later to the Korean War, in South Korea fundamentalists “became predominant and mainstream, marginalizing moderate and liberal churches” (Kim 2007, 175). With the help of authoritarian politicians, fundamentalists also acquired an influence on politics, economy, and the media that, in a large part, they still maintain today.

However, successful as they were, fundamentalist Protestants had to confront a challenge they did not expect, Christian new religious movements. Shincheonji, although perhaps not the largest, became the fastest growing among such movements. The fundamentalists reacted in a way typical of majority religions when they feel threatened by growing minorities. They accused successful minorities such as Shincheonji of “sheep stealing.” They also imported from Western anti-cultists theories, debunked decades ago by mainline scholars, claiming that “cults” do not grow through spontaneous conversions but because they master sinister and mysterious techniques of “brainwashing.”

A more simple explanation of the success of Christian new religious movements in South Korea is that many Koreans do like Christianity but do not feel comfortable with the cold, judgmental atmosphere of the fundamentalist churches, while they find the denominations in the liberal minority as too intellectual and cold in a different way. But of course, the fundamentalists do not accept this explanation, as it implies that there is something wrong in their presentation of Christianity. Instead, they create and promote organizations that fight “cults” and “heresies.”

By the 21st century, also due to their contacts with American groups of similar persuasions, conservative and fundamentalist Korean Protestants had learned the basic strategies of electoral politics and of forming broader coalitions. They are both anti-liberal and anti-cult, and the same agencies (often, the same persons) promote rallies, and occasionally resort to violence, against groups they label as “cults,” against homosexuals, and against Islamic refugees seeking asylum in Korea, Islam being considered by them a pagan and demonic religion, and one inherently inclined to terrorism.

Shincheonji is a main target of fundamentalist campaigns for one simple reason. It grows, and it grows often by converting members of fundamentalist churches. Apart from “heresy,” an accusation liberally traded between Christians since the times of the Apostles, Shincheonji has been accused of dissimulation. Indeed, Shincheonji does admit that Christians and others invited to its meetings are not immediately told that the organizer is Shincheonji, and that members sometimes attend services of other churches where they meet people whom they will later invite to Shincheonji meetings. The movement justifies this by explaining that opponents of Shincheonji spread derogatory information, thus causing a vicious circle. Because of the media slander and hostile propaganda, few would attend events if the name Shincheonji would be mentioned, as the movement is described negatively as problematic to society. In turn, the fact that the name of the church is not immediately advertised, and alternative names are sometimes used, is mentioned by critics as evidence that Shincheonji is a “cult,” which practices “dissimulation.” It is worth noting that introducing religious movements on the streets, particularly when they have been slandered by the media, without disclosing their name or by presenting first their non-religious cultural activities, is comparatively common in South Korea and not unique to Shincheonji.

Be it as it may be, in these times of quick access to information via the Internet, alternative names are easily connected to Shincheonji through a simple two- minute Google search. It is also absurd to claim that most converts to Shincheonji are deceived into joining it. Even those who accepted to attend a service or meeting without realizing the organizer was Shincheonji, obviously realize which religious movement they had encountered once they start listening to sermons and messages. Shincheonji is now increasingly switching to “open evangelism,” mentioning the name Shincheonji in all its invitations and activities.

This has not diminished the violence of anti-Shincheonji campaigns. Using their acquired political skills and connections, fundamentalists appeal to the secular arm and call for governmental actions against Shincheonji. They also take the law into their own hands and resort to violence. Deprogramming was a popular practice in the US in the 1970s. Parents complained that their adult children had been “brainwashed” by cults and hired professionals to abduct them and keep them confined and “counter-brainwashed,” until they renounced the “cult.” By the end of the 20th century, the practice had been reduced to a few isolated incidents after American and European courts ruled deprogramming was illegal.

In Japan, a special kind of deprogramming developed in the late 20th century. Rather than secular professionals, the deprogrammers were fundamentalist Protestant pastors. Members of the Unification Church and other “heretical” groups were abducted and confined by their parents and then “deprogrammed” by the pastors. It took several years for the Japanese courts to rule against deprogramming, but this finally happened in 2014.

In democratic countries, deprogramming only survives in South Korea, with thousands of cases. Victims are abducted and confined by the parents, and deprogrammed by Protestant pastors who work as professional deprogrammers. A dozen so-called cults are victims of deprogramming but the most targeted, with more than 2,000 cases, is Shincheonji. In 2018, a female Shincheonji member, Gu Ji-In (1992–2018), died as a cause of the second attempt at deprogramming her, after the first had failed. As she tried to escape, her parents bound and gagged her, causing suffocation. As a result, members of Shincheonji and other groups took to the street in massive demonstrations.

The U.S. Department of State reported in its Report on Religious Freedom published in 2019, and covering events of 2018, that, “In January, following reports that parents killed their daughter while attempting to force her to convert from what the parents viewed as a cult to their own Christian denomination. 120,000 citizens gathered in Seoul and elsewhere to protest against coercive conversion, reportedly conducted by some Christian pastors. The protestors criticized the government and churches for remaining silent on the issue and demanded action” (U.S. Department of State 2019).

Nevertheless, deprogramming continues, with numerous instances of violence and even attempts to confine abducted Shincheonji members in psychiatric hospitals. In 2019 only, Shincheonji has documented 116 cases of attempted deprogramming. Although inclined to regard them as “family affairs” they should not interfere with, Korean courts sometimes convict the parents—despite their adult children’s reluctance to denounce them in the context of a society where family is paramount—but never the deprogrammers, who normally do not participate in the kidnappings but instigate them, pocket sums that are in some cases exorbitant for their services, and are clearly accomplice to the unlawful detention and violence. One frequent defense by deprogrammers is that those kidnapped and detained sign declarations where they “consent” to deprogramming. This also happened in other countries, where courts quickly concluded that these documents were signed under duress and had no legal validity.

Deprogramming is not the only form of violence against Shincheonji. It is the most dramatic, but not the most widespread. Non-Koreans may have a hard time realizing how difficult it is to be a member of Shincheonji in South Korea. We collected hundreds of stories before the coronavirus crisis hit, of devotees who, when it was discovered that they were members of Shincheonji, were bullied in schools and colleges, or in the workplace. Some lost their jobs. This explains why members of Shincheonji tend not to reveal their religious affiliations to their friends and co-workers, and some hide it even in their families. Unfortunately, fundamentalist opponents to Shincheonji have succeeded in creating a widespread social hostility to the movement in South Korea. They have also tried to export it to other countries through both fundamentalist and anti-cult networks.

FACT

- Shincheonji grows by converting often members of fundamentalist Protestant churches.

- Shincheonji sometimes invited people to its activities without disclosing they were organized by Shincheonji or using alternative names, and its members attended services of other churches where they met people they would later invite to Shincheonji activities (although the movement is now replacing these practices with an “open evangelism” where the name Shincheonji is disclosed).

- Shincheonji’s fundamentalist opponents have used their political connections to call for governmental action against Shincheonji well before the virus crisis.

- Thousands of members of Shincheonji have been kidnapped and illegally detained to be “deprogrammed.”

FICTION

- It is not true that Shincheonji practices “brainwashing.” Indeed, mainline scholarship on new religious movements has debunked theories of brainwashing as pseudo-scientific since decades.

- It is not true that new converts are “deceived” into joining Shincheonji. In some cases, they might not have known that the organizer was Shincheonji when they were invited to a first meeting, but they quickly discovered it when they started listening to the messages and sermons.

- It is not true that Shincheonji members consent to be submitted to deprogramming, although they may sign “consent declarations” under duress.

4. Shincheonji, Suffering, and Illness

When the coronavirus crisis erupted, we read all sort of comments on Shincheonji’s theological positions about suffering and illness, ranging from the simply inaccurate to the outward silly. One problem is that journalists who were obviously not familiar with Christian theology wrote as if they had become amateur theologians overnight. They regarded as unique to Shincheonji theories about why humans suffer and die that are shared by millions of Christians. An otherwise authoritative magazine declared Shincheonji’s view of suffering “bad theology” (Park 2020). The word “ridiculous” was also liberally used for theological statements by Shincheonji that American reporters, in particular, might have easily encountered by simply attending a Sunday service in the Evangelical church next door, statements dozens of American senators and even politicians in higher positions would agree with.

Indeed, what is distinctive about Shincheonji’s theology of human suffering is that it is not distinctive. Certainly, other theological ideas of Shincheonji are original and far away from the Christian mainline, including that Chairman Lee is the promised pastor who will lead humanity into the Millennium, and that some of the events announced in the Book of Revelation already happened in South Korea. But this is not true for Chairman Lee’s teachings about suffering. They are shared by most conservative Protestant churches throughout the world.

Chairman Lee teaches that, as we read in the Bible, God did not want humans to suffer, get sick, and die. We can discover the source of these evils by reading the story of the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil in the Book of Genesis, the first book of the Bible. God told Adam and Eve not the eat the fruits of this tree in the Garden of Eden. Seduced by the Devil, the first progenitors did eat these fruits. As a consequence, suffering, sickness, and death entered the world. While some conservative and fundamentalist Christians would insist that this story should be intended literally, Chairman Lee teaches that “the fruits of the tree of knowledge of good and evil are clearly not real fruits” and “eating” them means “listening to and accepting Satan’s teachings,” which lead to perform the evil deeds that God regards as sins (Lee 2014, 94–5).

What happened in the Garden of Eden, Chairman Lee teaches, had dramatic consequences for all human history. Until the full restoration of God’s original covenant with humanity, we will continue to suffer and die. There is, however, hope. The Book of Revelation announces the Millennium, a world where there will be no illness, no suffering, no death. Those who will enter the Millennium will finally be liberated from these evils. These teachings are also common to a large number of conservative Protestant churches.

While the events leading to this glorious conclusion have already started unfolding (Lee 2004, 251), clearly, we have not yet entered the Millennium. Until the Millennium comes, the movement teaches, we continue to get sick and die, and this also applies to members of Shincheonji. While in the Millennium there will be no illness, for the time being we still get sick, and we need help in the shape of assistance, hospitals, and doctors. Some media confused Shincheonji’s hope in a future Millennium where illness will disappear with the present attitude of Shincheonji members toward illness.

Those of us who have studied Shincheonji have had the experience of meetings with its members postponed because they should visit a doctor or a dentist. HWPL donates relief money to support hospitals and medical care when disasters such as earthquakes and flood hit developing countries. Like all Christians, and indeed most devotees of all religions, Shincheonji members believe that prayer helps in time of sickness, if not by healing at least by helping the sick to live their painful experience with calm, patience, and hope. In some circumstances, sickness can be an opportunity for spiritual growth. But we never encountered in Shincheonji the idea that healthy Christians should seek illness and suffering to further their spiritual progress, a rare idea within Christianity, and one that was promoted by some within baroque 17th century Catholicism and promptly condemned by the Roman Catholic Church (de Certeau 1982). Shincheonji comes from a Protestant matrix, which is far away from a certain Catholic mysticism of suffering and its unorthodox excesses.

It has also been argued that by sitting on the floor next to each other rather than on chairs or pews, Shincheonji members hold their services in uniquely unhygienic conditions, more conductive to spreading bacteria and viruses. In fact, this also happens in several other religions. Most Islamic mosques and Buddhist or Hindu temples do not have chairs or pews either.

FACT

- Like millions of other Christians, Shincheonji believes that sickness and death originally came from sin, according to the symbolic story of Adam and Eve eating the forbidden fruits in the Garden of Eden.

- Like many other millennialist Christians, Shincheonji members expect sickness and death to disappear in the future Millennium.

- Until we will enter the Millennium, however, Shincheonji believes that we will all experience sickness, including members of Shincheonji, and while praying will certainly help, it is recommended to also seek the help of medical doctors and hospitals.

FICTION

- It is not true that Shincheonji members believe they are immune from sickness.

- It is not true that Shincheonji members do not seek medical help when needed.

- It is not true that Shincheonji’s services are uniquely unhygienic because participants sit on the floor rather than on chairs or pews; in fact, this is common in many religions.

5. Shincheonji and the Virus: Patient 31

The first case of coronavirus was detected in South Korea on January 20, 2020, when a Chinese woman who flew from Wuhan to Seoul was tested positive upon her arrival at Incheon Airport and quarantined (Reuters 2020). Shincheonji became involved in the crisis in the early morning of February 18, when a female Shincheonji member from the church’s Daegu congregation identified as Patient 31 tested positive.

Patient 31 was later blamed for not submitting to the test before. Some Korean media reported that she refused the test twice. She told a different story. On February 7, she was admitted to Saeronan Korean Medicine Hospital for a minor car accident and developed a cold, that she says was attributed to an open window in the hospital. Patient 31 insists that nobody mentioned coronavirus as a possibility to her, nor suggested a test. Only the following week, after her symptoms worsened, she was diagnosed with pneumonia, then tested for COVID-19. That, when quarantined, she started screaming and assaulted the nurse in charge in the hospital, was reported by some news but denied by both Patient 31 and the nurse.

Although speculations abound, at the time of this writing there is no clear evidence of how Patient 31 was infected. Some claim that she was infected by fellow Shincheonji members from China, or specifically, from Wuhan. The latter theory is unlikely to be true, considering that since 2018, due to opposition by the Chinese authorities, Shincheonji has not organized any gathering or worship services in Wuhan, although there are members there who keep in touch via the Internet. It is, however, true that from December 1, 2019, 88 Chinese Shincheonji members (none of them from Wuhan) entered South Korea. On February 21, 2020, Shincheonji submitted to the Korean Center for Disease Control and Prevention a list of these Chinese members and their movements. None of them had visited Daegu. On the other hand, there was no prohibition for Chinese visitors in general to enter Daegu. Shincheonji points out that a large group of Chinese students in school trip had visited Daegu prior to Patient 31’s first hospitalization.

There is no evidence that Patient 31 was aware that she was infected by the virus before she was tested on February 18. Allegations that she was offered a test before and refused may well be attempts by personnel at Saeronan Korean Medicine Hospital to defend themselves after it became obvious that theirs was a tragic mistake. Had Patient 31’s symptoms been recognized before as deriving from COVID-19 rather than from a common cold, she would have been quarantined on time. Instead, she continued her normal life and attended Shincheonji events and services, thus setting in motion a chain of events that eventually infected thousands of Shincheonji members.

One event that Patient 31 did not attend was the funeral of the elder brother of Chairman Lee, who died at Cheongdo Daenam Hospital on January 31, 2019. Rumors that she attended the funeral were denied by herself and Shincheonji, and even hostile media admitted there is no evidence that she did. Actually, the funeral issue is not crucial, as Shincheonji does not deny that Patient 31 infected other Shincheonji members. The only controversial matter is whether Patient 31 accepted to be tested for the virus the first time the test was proposed, as she claims, or only when the request was reiterated for the third time, as claimed by the doctors at Saeronan Korean Medicine Hospital—who at any rate could have placed her in forced quarantine before February 18, but didn’t. Even more important is how Shincheonji reacted to the crisis. It is not true that Shincheonji was not concerned about the epidemics. On January 25, and again on January 28, Shincheonji’s leadership issued orders that no Shincheonji members who had recently arrived from China to South Korea should be allowed to attend church services.

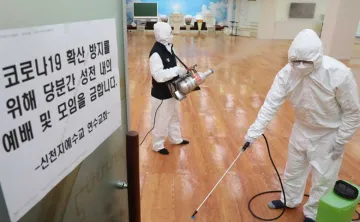

Shincheonji’s leaders in Daegu learned that Patient 31 was infected at 9 a.m. on February 18. The same day, Shincheonji closed all its centers in Daegu, and recommended that all its members there avoid also private gatherings and meetings, and went into self-quarantine. Later in the day, orders were issued to close all churches and mission centers throughout South Korea, and services continued only via the Internet. Shincheonji also suspended services and events abroad on February 22 and all forms of meetings, activities or gatherings in all countries on February 26.

On February 19, South Korean President Moon Jae-In stated that the government needed a full list of members of Shincheonji, and the most controversial phase of the crisis started.

FACT

- A female Shincheonji member from Daegu, Patient 31, tested positive to coronavirus on February 18, 2020.

- She had been hospitalized for a minor car accident on February 7 but not tested for the virus. Before being re-hospitalized, she attended Shincheonji functions and presumably infected other co- religionists, setting in motion a chain of events that ultimately led to thousands of Shincheonji members being infected.

- The same day Patient 31 tested positive, Shincheonji suspended all activities in churches and mission centers, first in Daegu and after a few hours throughout South Korea.

FICTION

- It is not true that Chinese Shincheonji members from Wuhan entered South Korea and infected Patient 31.

- There is no evidence that Patient 31 was infected by Shincheonji members from China (but not from Wuhan) who entered South Korea: some did, but none of them visited Daegu.

- There is no evidence that it was suggested to Patient 31 twice to be tested before February 18, and she refused. This was claimed by hospital doctors after February 18, when they were criticized for not having quarantined her before. She denies it.

- It is not true that Patient 31 assaulted a nurse and refused to be quarantined after she tested positive to the virus.

6. The Lists: Did Shincheonji Cooperate with the Authorities?

It is not surprising that fundamentalists, who operate from years anti-Shincheonji groups such as the so-called National Association of the Victims of Shincheonji Church, have collected signatures and filed suits asking for the dissolution of Shincheonji after the virus crisis. They simply hope that the virus may succeed where they consistently failed, i.e. in putting a halt to the growth of Shincheonji and to the movement’s annoying (for them) habit of converting their own members. It is also not very surprising that leaders of non-fundamentalist Christian churches have joined their voices to the attacks against Shincheonji. They have also seen their members converting to Shincheonji during the years, and such kind of competition is never welcome.

What is surprising, however, is that politicians at various levels, from city authorities to cabinet ministers, have also supported proposals to de-register Shincheonji as a religion, raid its churches, and file criminal lawsuits against its leaders, including Chairman Lee. South Korea is awaiting general elections in April 2020, and scapegoating an already unpopular group may be a convenient way for some politicians to distract attention from their own mistakes in handling the virus crisis. Fundamentalists, who hate Shincheonji, are a sizeable bloc of voters, and as mentioned earlier they succeeded in creating a diffuse hostility against the movement. Candidly, the Korean Minister of Justice admitted that there is no legal precedent for measures against Shincheonji, but she would consider adopting them because polls show they are supported by 86% of South Korean citizens (Shim 2020). Acting against a minority based on polls seems strange in a democracy, but the incident illustrates the level of anti-Shincheonji moral panic in South Korea.

Of what, exactly, Shincheonji is accused? There is considerable confusion in both Korean and international media. An old laundry list of accusations against “cults” is repeated—brainwashing, breaking families, and even misinterpreting the Bible—and mixed up with allegations that Shincheonji “did not cooperate” with the authorities.

Whatever the truth about Patient 31 and her tests, clearly Shincheonji cannot be held responsible for her dealings with the hospital authorities. Individual Shincheonji members have also been accused of hiding their affiliation with the movement when asked in schools and workplaces, and a “Deceptive Response Manual” instructing Daegu members how to credibly deny that they belong to Shincheonji has been published by some media. According to Shincheonji, the “Manual” was compiled by an individual member who, when the text became known to the local church leaders in Daegu, was reprimanded and referred to a disciplinary committee for having violated the church’s instructions to cooperate with the authorities. As we have seen, disclosing that one is a member of Shincheonji may have catastrophic consequences in South Korea. Yet, within the context of the virus crisis, Shincheonji’s instructions to members are to accept all requests by the authorities.

The basis of the allegation that Shincheonji did not fully cooperate with the Korean Center for Disease Control and Prevention (KCDC) after February 18 is that it did not entirely comply with the KCDC’s request to obtain a full list of the movement’s members. Establishing what exactly happened is thus important.

Although some religious organizations are better than others in keeping records of their members, we do not know of any organization that has complete lists of all its devotees with current addresses and with no omissions nor mistakes. Huge computers in the Vatican with the names and addresses of all Catholics in the world exist only in novels. Members may become inactive and move without telling the church of their new addresses. In Shincheonji, one may also be member of a church in one city while residing in another city, perhaps because he or she has friends there.

When President Moon himself stated that the government needed a list of all Shincheonji members, the movement started compiling lists, starting from Daegu. National lists were handed in six days from the request, on February 25. Controversies, however, had started even before.

In one province, it was alleged that there were two lists with a different number of members, and this was taken as evidence of Shincheonji’s lack of cooperation. Soon, it came out that one included the children of members, and the other didn’t.

The government objected that the list of February 25 included less members than those mentioned in Shincheonji’s official statistics. But the latter also count foreign members, and Shincheonji had understood that the KCDC needed only data about members in South Korea. Why exactly Korean authorities need to know the names of Shincheonji members in Europe or North America is unclear but, when they asked for the lists of foreign members, they received them as well.

The main problem concerned “students,” which is the name Shincheonji uses for people that are not members of the church but attend courses and other activities in the mission centers and may (or may not) one day join the church. Shincheonji had records of 54,176 such “students” in South Korea and 10,951 abroad. It also had serious privacy concerns about them. Notwithstanding the promises of the authorities, some lists of members had been leaked to the media. This was bad enough, but if one becomes a member of Shincheonji in South Korea (not necessarily abroad), he or she is aware of the risks this involves. The same is not true for “students.” In fact, they may evaluate the risks and decide not to join—and of course the risks are higher now after anti-Shincheonji hostility peaked with the virus crisis. Shincheonji’s hesitation in disclosing the names of “students” was thus understandable. It is also understandable that health authorities believed that those who attended Shincheonji centers were all equally at risk to be infected, be they members or “students.” On February 27, the KCDC formally requested the list of “students,” and undertook to assume legal responsibility for any possible breach of privacy and related consequences. The list was handed the same day.

All this work involved communicating to the government lists involving some 300,000 names and addresses. That the exercise might have been entirely free of mistakes was beyond human possibilities, but the mistakes the authorities found do not indicate bad faith by Shincheonji.

Opponents took the opportunity to tell the media that there should be somewhere lists of those Shincheonji members who attend other Christian churches without disclosing their Shincheonji affiliation in an endeavor to make friends there and proselytize. The practice has been discussed above, but Shincheonji’s position is that, no matter what they are currently doing, if they are members of Shincheonji they should be registered as such with one of the tribes.

Parallel problems concerned the government’s request of a full list of real estate owned or rented by Shincheonji. This, again, was less simple that it may seem. Real estate is owned or rented by a variety of different legal entities, some of them connected with Shincheonji’s headquarters and others with one of the twelve tribes. Shincheonji supplied initially a list of 1,100 properties, which the authorities objected to as been incomplete. They also complained that some addresses were wrong, and in fact further investigation by Shincheonji found that 23 of the listed properties had been shut down. Later, Shincheonji reported that the total number of properties owned or rented was 1,903, including the 23 shut down, but this number included parcels of land, warehouses, and private houses and shops owned and rented that were not used by Shincheonji members for any gathering or meeting.

FACT

- Shincheonji provided the list of its South Korean members six days after it was requested. It added the lists of foreign members and “students” when they were requested, and after the government assumed legal responsibility for possible breaches of privacy.

- Lists including hundreds of thousands of names and addresses had to be quickly compiled and checked, and some mistakes occurred.

- When the government asked for the lists of real estate owned or rented by Shincheonji, it was initially unclear whether shut down facilities, and properties where no members gathered, should be included.

FICTION

- There is no evidence that mistakes in the lists were intentional, and they are statistically common when all such massive lists are compiled.

- There is no evidence that Shincheonji intentionally delayed the compilation and handing of the lists.

- There is no evidence that secret lists of Shincheonji members operating undercover in other churches exist elsewhere than in the fantasy of Shincheonji’s opponents.

7. Conclusion: Criminal Negligence or Scapegoating?

On March 2, 2020, Chairman Lee held a press conference, in which he apologized for the mistakes Shincheonji might have committed and even knelt before the reporters. For those of us who have interviewed him, and no doubt much more for the members, the sight of an 89-year-old religious leader kneeling in front of a crowd including people who had vilified and slandered him for years was deeply moving. It may also be misinterpreted. In our Western mindset, leaders rarely apologize, and we tend to believe that, when they do, they should really be guilty. But the East Asian tradition is different. Leaders take responsibility for their subordinates, and a leader is appreciated if he or she shows humility.

Did Shincheonji make mistakes? Chairman Lee’s answer was yes. The rhetoric of his press conference should be understood, yet, for all the practical problems we mentioned in the previous paragraph, it is also possible that Shincheonji was slow to realize the magnitude of the crisis, which went well beyond Patient 31 and threatened its very existence and future, as well as the public health of millions of Koreans. Probably some mistakes and delays in compiling lists and working with the authorities could not have been avoided, but others were avoidable.

Mistakes, however, should not be confused with crimes. Shincheonji could have answered some requests of the authorities in a quicker and better way, but it operated under extreme pressure and in very difficult circumstances. South Korean vice-minister of Health, Kim Kang-lip, told the media that, “no evidence has been found that Shincheonji supplied missing or altered lists,” and that between the list collected and checked by the government and those supplied by Shincheonji “there were only minor differences,” which could be explained with different ways of counting members, and whether minor children of members were included or not (Lee 2020).

One of the most distinguished East Asian sociologists of religions, professor Yang Fenggang, offered a rare voice of common sense when he told the South China Morning Post that, “I think there is no necessary link between Shincheonji and coronavirus spread in South Korea. It is accidental that this large religious group happened to have some infected people who infected others through religious gatherings or individual interactions. There are many megachurches in South Korea, some are huge, with hundreds of thousands of members. Any of these evangelical or Pentecostal megachurches could have had such an accident” (Lau 2020).

As for the individual members of Shincheonji who did not volunteer to disclose their affiliation with the movement until the authorities arrived at them through the list, and tried to hide it to the bitter end notwithstanding the movement’s instruction called for cooperation, before judging their behavior one should consider that they were risking their jobs.

And perhaps their lives. In Ulsan, on February 26, a Shincheonji female member died after falling from a window on the 7th floor of the building where she lived. The incident occurred where her husband, who had a history of domestic violence, was attacking her and trying to compel her to leave Shincheonji (Moon 2020). At the time of this writing, the police are investigating possible foul play.

This lethal incident is just the tip of an iceberg. Shincheonji claims that, after the case of Patient 31, more than 4,000 instances of discriminations against its members occurred in South Korea, and the number continues to grow. Being identified as a member of Shincheonji leads to the serious risk of being harassed, bullied, beaten, or fired from one’s job. For the opponents, the virus is the opportunity for a “final solution” of the “problem” of Shincheonji.

On February 6, 2020, the U.S Commission for International Religious Freedom, a commission of the U.S. federal government whose members are appointed by the President of the United States and the leadership of both political parties in the Senate and the House of Representatives, issued a declaration stating that, “USCIRF is concerned by reports that Shincheonji church members are been blamed for the spread of #coronavirus. We urge the South Korean government to condemn scapegoating and to respect religious freedom as it responds to the outbreak.” We wholeheartedly subscribe to this conclusion and appeal. The virus cannot be an excuse to violate the human rights and religious liberty of hundreds of thousands of believers.

FACT

- Shincheonji made some mistakes in its cooperation with the authorities, for which Chairman Lee apologized in a press conference.

- Thousands of cases of discrimination against innocent Shincheonji members occurred in South Korea after the coronavirus crisis started.

FICTION

- It is not true that Shincheonji’s delays and mistakes amount to criminal negligence or a deliberate attempt to boycott the authorities’ efforts.

- It is not true that actions against Shincheonji are sought by opponents to better protect Koreans against the virus; instead, they pursue the aim of destroying Shincheonji, something Christian fundamentalists have tried to do for decades.

References

de Certeau, Michel. 1982. La Fable mystique. Vol. 1, XVIe-XVIIe siècle. Paris

Gallimard. Gottfried, Robert S. 1983. Black Death: Natural and Human Disaster in Medieval Europe. New York: The Free Press.

Introvigne, Massimo. 2019. “Shincheonji.” World Religions and Spirituality Project, August 30. Accessed March 9, 2020. https://wrldrels.org/2019/08/29/shincheonji/.

Kim, Chang Han. 2007. “Towards an Understanding of Korean Protestantism: The Formation of Christian-Oriented Sects, Cults, and Anti-Cult Movements in Contemporary Korea.” Ph.D. diss. University of Calgary.

Lau, Mimi. 2020. “Coronavirus: Wuhan Shincheonji Member Says Church Followed Quarantine Rules.” South China Morning Post, March 4. Accessed March 9, 2020. https://www.scmp.com/news/china/society/article/3064766/coronavirus-wuhan-shincheonji-member-says-church-followed.

Lee, Man Hee. 2014. The Creation of Heaven and Earth. Second English edition. Gwacheon, South Korea: Shincheonji Press.

Lee, Min-jung. 2020. “추미애 “신천지 강제수사···‘중대본 “방역도움 안된다’” (Chu Mi-ae: ‘Forced Investigation of Shincheonji’). Joongang Daily, March 2. Accessed March 9, 2020. https://news.joins.com/article/23719806?cloc=joongang-mhome-group1.

Moon, Hee Kim. 2020. “신천지 교인 추락사..종교 문제로 부부싸움” (Shincheonji Church: Married Couple Fought Over Religious Issues). UMSBC, February 27. Accessed March 9, 2020. https://usmbc.co.kr/article/aJnwcqGVt4.

Naphy, William G. 2002. Plagues, Poisons, and Potions: Plague-spreading Conspiracies in the Western Alps, c. 1530–1640. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press.

Naphy, William G. 2003. Calvin and the Consolidation of the Genevan Reformation. With a New Preface. Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press.

Nicolini, Fausto. 1937. Peste e untori nei “Promessi Sposi” e nella realtà storica. Bari: Laterza.

Park, S. Nathan. 2020. “Cults and Conservatives Spread Coronavirus in South Korea.” Foreign Policy, February 27. Accessed on March 8, 2020. https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/02/27/coronavirus-south-korea-cults-conservatives-china/.

Reuters. 2020. “South Korea Confirms First Case of New Coronavirus in Chinese Visitor.” January 20. Accessed on March 8, 2020. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-health-pneumonia-south-korea/south-korea-confirms-first-case-of-new-coronavirus-in-chinese-visitor-idUSKBN1ZJ0C4.

Shim, Elizabeth. 2020. “South Korea Authorizes Raid of Shincheonji Amid COVID-19 Outbreak.” UPI, March 4. Accessed March 8, 2020. https://www.upi.com/Top_News/World-News/2020/03/04/South-Korea-authorizes-raid-of-Shincheonji-amid-COVID-19-outbreak/5871583330375/.

Graduation ceremony in November 2019