The session "Gnosticism and New Religions: The Case of L. Ron Hubbard" held on August 30th during the first day of the annual meeting of the European Academy of Religions at the University of Münster (Germany), was chaired and moderated by a member of our Scientific Committee: Rosita Šorytė; one of the speakers, Professor Aldo Natale Terrin, is also part of the same Committee.

It is therefore necessary to give space to this article written for Bitter Winter by FOB's President Alessandro Amicarelli. But this is not the only reason for publishing this paper. As masterfully explained by Massimo Introvigne, director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), the "anti-cult" movements have always practiced what the Anglo-Saxons call the "assassination of character", that is, the systematic activity of debasing the reputation of the leaders of religious movements they dislike. With Hubbard they have done so several times in an attempt to spread a morally abject image of him. This questionable activity carried out, for example, in 1969 by the Sunday Time journalist Alex Mitchel, continues after more than half a century by modern "anti-cults" such as the controversial FECRIS (European Federation of Research and Information Centers on Sectarianism) and the large and small associations that represent it in several European and non-European countries. It is certainly an activity aimed at infringing the right to freedom of belief, therefore of our interest.

Gnosticism, “Dark Legends” on Scientology Founder Discussed by Scholars

by Alessandro Amicarelli — On August 30, 2021, a session at the European Academy of Religion 2021 conference in Münster, Germany, was devoted to “Gnosticism and New Religions: The Case of L. Ron Hubbard,” with some speakers connected via the Internet.

Rosita Šorytė, a member of the Scientific Committee of the European Federation for Freedom of Belief (F.O.B.), and the author of several studies about Scientology, introduced the session observing that, during the COVID-19 pandemic, several new religious movements, including Scientology, helped with impressive humanitarian activities, yet rarely did they get credit for it. On the other hand, she observed, during a global crisis religions are expected to do more than help materially, they are asked to offer hope and meaning. Šorytė noted that during the pandemic Scientology invited its members and the general public to read a text by its founder L. Ron Hubbard on “dangerous environments,” from where readers can derive what she calls “a Gnostic narrative of the pandemic.”

Scientology teaches that the basic essence of humans is an immortal spiritual being, known as thetan, who—in what Šorytė characterized as a typical Gnostic theory—forgot that they are cause rather than effect of the universe, and should be reminded of it. By reconquering the awareness of their immortal nature, the thetans also dispel the fear of the crises, and confront them in the most effective way.

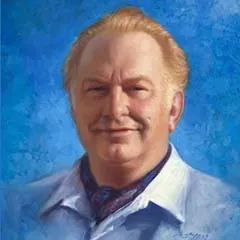

L. Ron Hubbard (1911–1986), portrait by Peter Green (1999).

The first paper was presented by Aldo Natale Terrin, a Roman Catholic priest who teach at the Santa Giustina Institute in Padua, and the author of an important book about Scientology. He said that while others have compared Scientology to Eastern religions, the closest comparison is indeed Gnosticism. Terrin examined the popular definition of Gnosticism by Dutch scholar Gilles Quispel, one of the greatest specialist of ancient Gnostic schools, as a “mythical expression of self-awareness.” The insistence on “self-awareness,” Terrin said, immediately indicates that Quispel’s was a psychological approach to defining Gnosticism, one the Dutch scholar came to through his decade-long dialogue with psychoanalyst Carl Gustav Jung.

Aldo Natale Terrin participating in the session via Web.

Jung himself, Terrin added, had a deep interest in Gnosticism, and even wrote an enigmatic text in the tradition of the Gnostic hymns, the Seven Sermons to the Dead. However, Terrin noted, we also know that Jung never allowed the manuscript of the Seven Sermons to be published during his lifetime, either because he was displeased with it or he regarded it as too controversial.

What is important in Jung’s and Quispel’s approach for the question of Hubbard’s own Gnosticism, Terrin suggested, is the idea that Gnostics are part of a broader tradition of “perennial wisdom,” rooted in what Italian 16th-century humanist Agostino Steuco called “prisca theologia,” the ancient “theology” common to all great religions.

Here, according to Terrin, is the link between Gnosticism, and its interpretation by Jung and Quispel, and L. Ron Hubbard. “Perennial philosophy is the connection between Gnosticism and Scientology,” Terrin concluded, both because Hubbard is part of this tradition and he theorized that the truth of all legitimate religions is one. We can thus also reconcile the theory that Scientology is rooted in Eastern religions, Terrin noted, and the idea that it is a modern Gnostic faith. In fact, both Gnosticism and the Eastern religions share a fundamental insistence on self-awareness, and contemporary Dutch scholar Wouter Hanegraaff has called the ancient wisdom tradition a “Platonic orientalism.”

Massimo Introvigne, managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR) and editor-in-chief of Bitter Winter, discussed how those hostile to Scientology try to take advantage of Hubbard’s early exploration of several Gnostic traditions and movements to claim that he was associated with “black magic.”

They refer to Hubbard’s exploration in 1945–46 of Pasadena’s Agapé Lodge, led by Cal Tech rocket scientist Jack Parsons, of the Ordo Templi Orientis (O.T.O.), whose international leader was British magus Aleister Crowley. Although Hubbard lived in Parsons’ mansion and participated in the Lodge’s activities, the association was short-lived and would have been forgotten if a British Trotskyist journalist called Alex Mitchell had not published in 1969 an expose in London’s Sunday Times connecting Hubbard with Crowley’s “black magic.”

Jack Parsons (credits)

Hubbard replied with a letter to the Sunday Times where he claimed that in fact he was spying on Parsons’ group and reporting to the American intelligence, and eventually “broke up” the “black magic” ring and put an end to the “savage and bestial rites” of Aleister Crowley’s O.T.O. in California.

Critics of Hubbard contrast this letter with the fact that in 1952 in two lectures Hubbard had called Crowley a “good friend,” and had discussed his theory of magic as “a splendid piece of aesthetics,” an attempt to go beyond the materialistic approach to cause and effect, although one rooted in rituals and belief, which normally do not succeed in overcoming materialism.

Introvigne referred to American scholar J. Gordon Melton who concluded that the facts that Hubbard was informing people connected with the American intelligence and concerned about the fact that a scientist working for the military such as Parsons was involved in strange activities, and that the founder of Scientology had a genuine curiosity about Crowley’s ideas may both be true, as one does not necessarily exclude the other.

Introvigne noted that if we read Hubbard’s fiction, we realize that he was interested in magic and had declared magic’s attempt to overcome materialism praiseworthy but at the same time doomed to fail because of its roots in ritual and belief, some twenty years before meeting Parsons. Introvigne also noted that the situation in 1969, when Hubbard was attacked by the Sunday Times, was totally different from the 21st century. Today, even if anti-cultists seem not to realize it, there are several academic books and university courses discussing Crowley’s ideas, and even tenured academics who are themselves members of the O.T.O. In 1969, indeed, the image of Crowley was simply one of a black magician engaged in “savage and bestial rites,” while in 2021 his academic image is of a brilliant esoteric thinker, although one prone to indefensible behavior and with an unpalatable private life.

Both Hubbard’s assessment of magic and of Crowley, Introvigne concluded, were surprisingly modern, and much closer to modern academic studies than the journalistic opinions of his times. On the one hand, Crowley often behaved in a “savage and bestial” way, but at the same time his theory of magic has become a legitimate object of academic study both for its comprehensiveness and its elegance—“a splendid piece of aesthetics” indeed.

Eric Roux, chair of the European Interreligious Freedom for Religious Freedom and himself a Scientologist, offered an insider view of Hubbard’s Gnosticism. He noted that in a 1955 article, “The Scientologist: a Manual on the Dissemination of Material,” Hubbard wrote that, “As Scientologists, we are gnostics, this is to say that we know that we know.” He contrasted this with the religions (and magical systems) who “believe in belief,” while Scientology comes from an “older tradition,” of which ancient Gnosticism was also part.

Eric Roux at the session

Hubbard, Roux said, had a Gnostic theory of the fall, where the thetans lost what they once knew, and one of the recovery of complete knowledge, something the founder of Scientology called “knowingness.”

If Scientology is Gnosticism, Roux noted, it is a Gnosticism of the 20th century. Its tool to achieve what it calls knowingness are not the same as they were in the ancient Gnostic schools. Roux quoted Catholic theologian and historian Michel de Certeau, who stated he admired Scientology’s “articulation between ethical concerns, a search for wisdom, and technical learning.”

In Scientology, added Roux, there is a precise technology for knowingness, although it includes references to themes who were already of interest to the ancient Gnostics, including reincarnation and the immortality of the soul. Ultimately, Hubbard’s Gnosticism teaches to “know how to know,” which ultimately leads to “know that you know.”

Like other intellectual adventures that are part of the tradition of Western Esotericism, Hubbard’s exploration of Gnosticism and theorization of a modern form of it needs to be studied within the broader context of what some have called the modern “return of the Gnosis.” Reducing them to some anecdotes about Hubbard’s encounters with modern Gnostic movements is part of gossip rather than of scholarship.

Source Bitter Winter